Teaching Holocaust history demands a high level of sensitivity and keen awareness of the complexity of the subject matter. The following guidelines from the USHMM, while reflecting approaches appropriate for effective teaching in general, are particularly relevant to Holocaust education.

Define the term “Holocaust”

The Holocaust was the systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators. During the era of the Holocaust, German authorities also targeted other groups because of their perceived “racial inferiority”: Roma (Gypsies), the disabled, and some of the Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, and others). Other groups were persecuted on political, ideological, and behavioral grounds, among them Communists, Socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and homosexuals.

Do not teach or imply that the Holocaust was inevitable

Just because a historical event took place, and it is documented in textbooks and on film, does not mean that it had to happen. This seemingly obvious concept is often overlooked by students and teachers alike. The Holocaust took place because individuals, groups, and nations made decisions to act or not to act. Focusing on those decisions leads to insights into history and human nature and can help your students to become better critical thinkers.

Avoid simple answers to complex questions

The history of the Holocaust raises difficult questions about human behavior and the context within which individual decisions are made. Be wary of simplification. Seek instead to convey the nuances of this history. Allow students to think about the many factors and events that contributed to the Holocaust and that often made decision making difficult and uncertain.

Strive for Precision of Language

Any study of the Holocaust touches upon nuances of human behavior. Because of the complexity of the history, there is a temptation to generalize and, thus, to distort the facts (e.g., “all concentration camps were killing centers” or “all Germans were collaborators”). Avoid this by helping your students clarify the information presented and encourage them to distinguish, for example, the differences between prejudice and discrimination, collaborators and bystanders, armed and spiritual resistance, direct and assumed orders, concentration camps and killing centers, and guilt and responsibility.

Words that describe human behavior often have multiple meanings. Resistance, for example, usually refers to a physical act of armed revolt. During the Holocaust, it also encompassed partisan activity; the smuggling of messages, food, and weapons; sabotage; and actual military engagement. Resistance may also be thought of as willful disobedience, such as continuing to practice religious and cultural traditions in defiance of the rules or creating fine art, music, and poetry inside ghettos and concentration camps. For many, simply maintaining the will to live in the face of abject brutality was an act of spiritual resistance.

Try to avoid stereotypical descriptions. Though all Jews were targeted for destruction by the Nazis, the experiences of all Jews were not the same. Remind your students that, although members of a group may share common experiences and beliefs, generalizations about them without benefit of modifying or qualifying terms (e.g., “sometimes,” “usually,” “in many cases but not all”) tend to stereotype group behavior and distort historical reality. Thus, all Germans cannot be characterized as Nazis, nor should any nationality be reduced to a singular or one-dimensional description.

Strive for balance in establishing whose perspective informs your study of the Holocaust

Most students express empathy for victims of mass murder. However, it is not uncommon for students to assume that the victims may have done something to justify the actions against them and for students to thus place inappropriate blame on the victims themselves. One helpful technique for engaging students in a discussion of the Holocaust is to think of the participants as belonging to one of four categories: victims, perpetrators, rescuers, or bystanders. Examine the actions, motives, and decisions of each group. Portray all individuals, including victims and perpetrators, as human beings who are capable of moral judgment and independent decision making.

As with any topic, students should make careful distinctions about sources of information Students should be encouraged to consider why a particular text was written, who wrote it, who the intended audience was, whether any biases were inherent in the information, whether any gaps occurred in discussion, whether omissions in certain passages were inadvertent or not, and how the information has been used to interpret various events. Because scholars often base their research on different bodies of information, varying interpretations of history can emerge. Consequently, all interpretations are subject to analytical evaluation. Strongly encourage your students to investigate carefully the origin and authorship of all material, particularly anything found on the Internet.

Avoid comparisons of pain

A study of the Holocaust should always highlight the different policies carried out by the Nazi regime toward various groups of people; however, these distinctions should not be presented as a basis for comparison of the level of suffering between those groups during the Holocaust. One cannot presume that the horror of an individual, family, or community destroyed by the Nazis was any greater than that experienced by victims of other genocides. Avoid generalizations that suggest exclusivity such as “The victims of the Holocaust suffered the most cruelty ever faced by a people in the history of humanity.”

Do not romanticize history

People who risked their lives to rescue victims of Nazi oppression provide useful, important, and compelling role models for students. But given that only a small fraction of non-Jews under Nazi occupation helped rescue Jews, an overemphasis on heroic actions in a unit on the Holocaust can result in an inaccurate and unbalanced account of the history. Similarly, in exposing students to the worst aspects of human nature as revealed in the history of the Holocaust, you run the risk of fostering cynicism in your students. Accuracy of fact, together with a balanced perspective on the history, must be a priority.

Contextualize the history

Events of the Holocaust, and particularly how individuals and organizations behaved at that time, should be placed in historical context. The Holocaust must be studied in the context of European history as a whole to give students a perspective on the precedents and circumstances that may have contributed to it.

Similarly, the Holocaust should be studied within its contemporaneous context so students can begin to comprehend the circumstances that encouraged or discouraged particular actions or events. For example, when thinking about resistance, consider when and where an act took place; the immediate consequences of one’s actions to self and family; the degree of control the Nazis had on a country or local population; the cultural attitudes of particular native populations toward different victim groups historically; and the availability and risk of potential hiding places.

Encourage your students not to categorize groups of people only on the basis of their experiences during the Holocaust; contextualization is critical so that victims are not perceived only as victims. By exposing students to some of the cultural contributions and achievements of 2,000 years of European Jewish life, for example, you help them to balance their perception of Jews as victims and to appreciate more fully the traumatic disruption in Jewish history caused by the Holocaust.

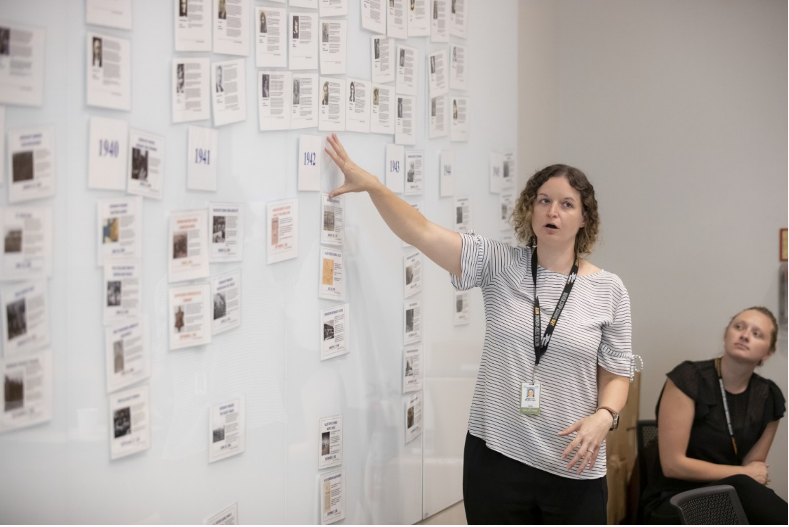

Translate statistics into people

In any study of the Holocaust, the sheer number of victims challenges easy comprehension. Show that individual people—grandparents, parents, and children—are behind the statistics and emphasize the diversity of personal experiences within the larger historical narrative. Precisely because they portray people in the fullness of their lives and not just as victims, first-person accounts and memoir literature add individual voices to a collective experience and help students make meaning out of the statistics.

Make responsible methodological choices

One of the primary concerns of educators teaching the history of the Holocaust is how to present horrific, historical images in a sensitive and appropriate manner. Graphic material should be used judiciously and only to the extent necessary to achieve the lesson objective. Try to select images and texts that do not exploit the students’ emotional vulnerability or that might be construed as disrespectful to the victims themselves. Do not skip any of the suggested topics because the visual images are too graphic; instead, use other approaches to address the material.

In studying complex human behavior, many teachers rely upon simulation exercises meant to help students “experience” unfamiliar situations. Even when great care is taken to prepare a class for such an activity, simulating experiences from the Holocaust remains pedagogically unsound. The activity may engage students, but they often forget the purpose of the lesson and, even worse, they are left with the impression that they now know what it was like to suffer or even to participate during the Holocaust. It is best to draw upon numerous primary sources, provide survivor testimony, and refrain from simulation games that lead to a trivialization of the subject matter.

Furthermore, word scrambles, crossword puzzles, counting objects, model building, and other gimmicky exercises tend not to encourage critical analysis but lead instead to low-level types of thinking and, in the case of Holocaust curricula, trivialization of the history. If the effects of a particular activity, even when popular with you and your students, run counter to the rationale for studying the history, then that activity should not be used.